Low emission zones: A Solution to control urban air pollution in Vietnam

Latest

|

| Many countries worldwide have adopted the “Low Emission Zone” model. (Source: Dayinsure) |

Air pollution in major Vietnamese cities has reached alarming levels, threatening public health and causing severe economic consequences. During this situation, the LEZ model — already proven effective in many cities worldwide — is increasingly mentioned as a necessary solution, though its implementation remains challenging.

A Traffic Regulation Solution for Urban Health and Environment

An LEZ is an urban area where high-emission vehicles, usually old or non-compliant with emission standards, are restricted or banned from entry. The main goal is to reduce harmful emissions, particularly NO₂, CO₂, and fine particulate matter (PM2.5), thereby improving air quality and protecting public health.

Unlike Zero Emission Zones (ZEZ) which only allow electric vehicles, bicycles, and pedestrians, LEZs are more flexible. Many cities use fees to regulate vehicle entry rather than outright bans. This approach ensures social feasibility while generating revenue to reinvest in green transport infrastructure.

LEZs are not a new concept. Europe pioneered this model in the early 2000s, and today hundreds of LEZs operate in Germany, France, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, and more. In Asia, China, Republic of Korea, and Singapore are frontrunners. In the United States, LEZs are selectively implemented, mainly in California — a state known for the strictest environmental standards in the country.

|

| Glasgow became the first city in Scotland to adopt the LEZ model. (Source: Scottish Express) |

The effectiveness of LEZs is well documented by scientific studies and real-world data. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), air pollution causes over 7 million premature deaths annually. Respiratory diseases, cardiovascular conditions, and cancers are closely linked to urban air quality. Fine PM2.5 particles can penetrate lung membranes, enter the bloodstream, and trigger chronic inflammation and serious complications.

Research from Imperial College London showed that, after implementing LEZs, NO₂ concentrations in central London dropped by over 44% in ten years, while PM10 emissions from buses decreased by nearly 90%. Similarly, Berlin reduced diesel particulate matter — the most hazardous component of airborne particles — by more than 58%.

Beyond health benefits, LEZs also lower healthcare costs, boost productivity, and reduce traffic congestion. A study in Milan estimated that the city saved nearly €20 million annually due to reduced pressure on healthcare and environmental expenses.

Diverse Models, Proven Effectiveness

Each country implements LEZs differently, depending on pollution levels, economic conditions, and public transport systems.

In Germany, to enter an LEZ (known as Umweltzone), vehicles must display a green environmental sticker (Feinstaubplakette), which can be purchased online or at certain car dealerships. Some cities ban diesel vehicles that fail to meet Euro 5 or Euro 6 standards on specific streets or urban areas.

In the Netherlands, cities such as Amsterdam, Arnhem, The Hague, and Utrecht have established LEZs called milieuzones, banning diesel vehicles that do not meet at least Euro 3 or Euro 4 standards.

Cameras are installed at intersections to detect license plates. Vehicles meeting emission standards receive a green sticker allowing entry, while those with a red sticker must leave the area. Violators face fines of €140 for the first offense, €500 for the second, and up to €800 for repeated violations.

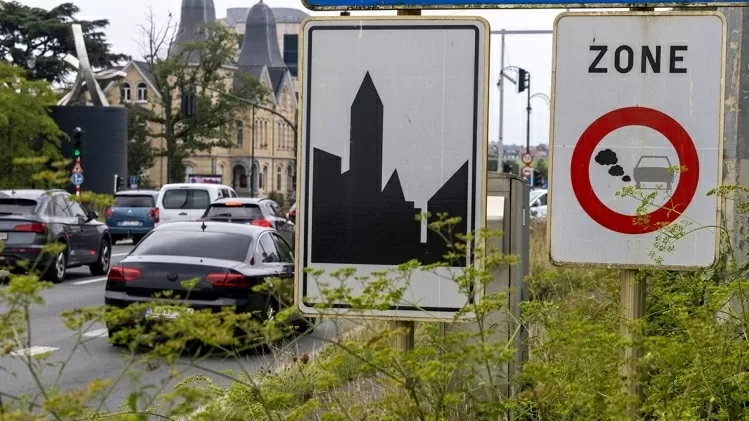

|

| LEZs have proven effective in many cities worldwide. (Source: Belga) |

In Belgium, since 2018, diesel vehicles, light trucks, and light service vehicles with Euro 4 or lower standards have been banned from entering Brussels’ LEZ. Offenders are fined €350. Thanks to this policy, the city reduced diesel vehicles by 62% in 2018, and by 2020, 50% of diesel vehicles were replaced by hybrid engines.

In Milan, Italy, a toll-based LEZ model (Area C), introduced in 2012, cut traffic by 30% and reduced CO₂ emissions by over 35% in the city center.

Paris, once among the most polluted European capitals, has almost entirely phased out old diesel cars thanks to LEZ policies combined with electric vehicle incentives and expanded cycling infrastructure. The city bans non-compliant personal vehicles from 8 AM to 8 PM daily, while prioritizing public service vehicles.

In Asia, China has implemented LEZs in cities such as Shenzhen, Foshan, Dongguan, and Hangzhou, combined with random inspections and on-the-spot fines.

Singapore does not formally call it an LEZ but enforces high vehicle taxes, periodic emission checks, and an Electronic Road Pricing (ERP) system, which regulates vehicle entry into the city center at different time slots.

In Seoul, South Korea, old cars and diesel vehicles that fail emission standards are restricted or banned from entering LEZs, with fines of up to 250,000 won (around US$180).

A Possible Scenario for Vietnam’s Green Transport Strategy

In Vietnam, air pollution is becoming an urgent issue in many major cities. Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City frequently rank among the world’s most polluted cities, with AQI (Air Quality Index) often exceeding hazardous levels for consecutive days.

Data from the Department of Environment (Ministry of Agriculture and Environment) shows PM2.5 concentrations in Hanoi reaching 150 µg/m³ — three times higher than WHO’s recommended limit. The main culprits are motorized traffic, particularly old motorcycles and diesel trucks with uncontrolled emissions, compounded by construction dust and high population density.

|

| A thick layer of smog blankets high-rise buildings and apartment complexes in Hanoi. (Source: Bao Lao dong) |

Meanwhile, public transport infrastructure remains insufficient, forcing people to rely on personal vehicles. The lack of synchronized infrastructure, emission inspection stations, and practical application of Euro standards exacerbates the challenge.

While LEZs offer significant benefits, their implementation in Vietnam cannot be rushed. Authorities should first identify and pilot LEZs in areas with high traffic density and poor air quality, such as inner districts of Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, gradually expanding them after evaluating results.

Vietnam should also consider mandating Euro 4, 5, or 6 emission standards for new vehicles and phase out non-compliant ones. Air quality monitoring stations, congestion charges, and camera-based supervision are essential for effective LEZ operation.

Public transport — especially electric buses and urban railways — must be accelerated in parallel with policies supporting personal vehicle transition. Incentives for electric and hybrid cars, such as tax reductions, registration fee exemptions, and credit support, should be introduced. Moreover, strong public awareness campaigns are crucial to help citizens understand the benefits and participate in this green transition.

Low Emission Zones are not merely a technical solution but a pillar of sustainable urban development. Vietnam cannot stand apart as other nations “green” their transportation systems. The longer the delay, the higher the cost in health, environmental damage, and national reputation.

Implementing LEZs will be challenging, requiring cross-sector coordination, long-term investment, and societal behavior changes. Yet, prioritizing human health and community well-being makes this a transformation worth starting today.