The interpreter of the Paris Peace Talks - A silent journey at the heart of history

Latest

|

| Nguyen Dinh Phuong (centre) interpreted for the meeting between Special Adviser Le Duc Tho and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger. (Photo: A courtesy) |

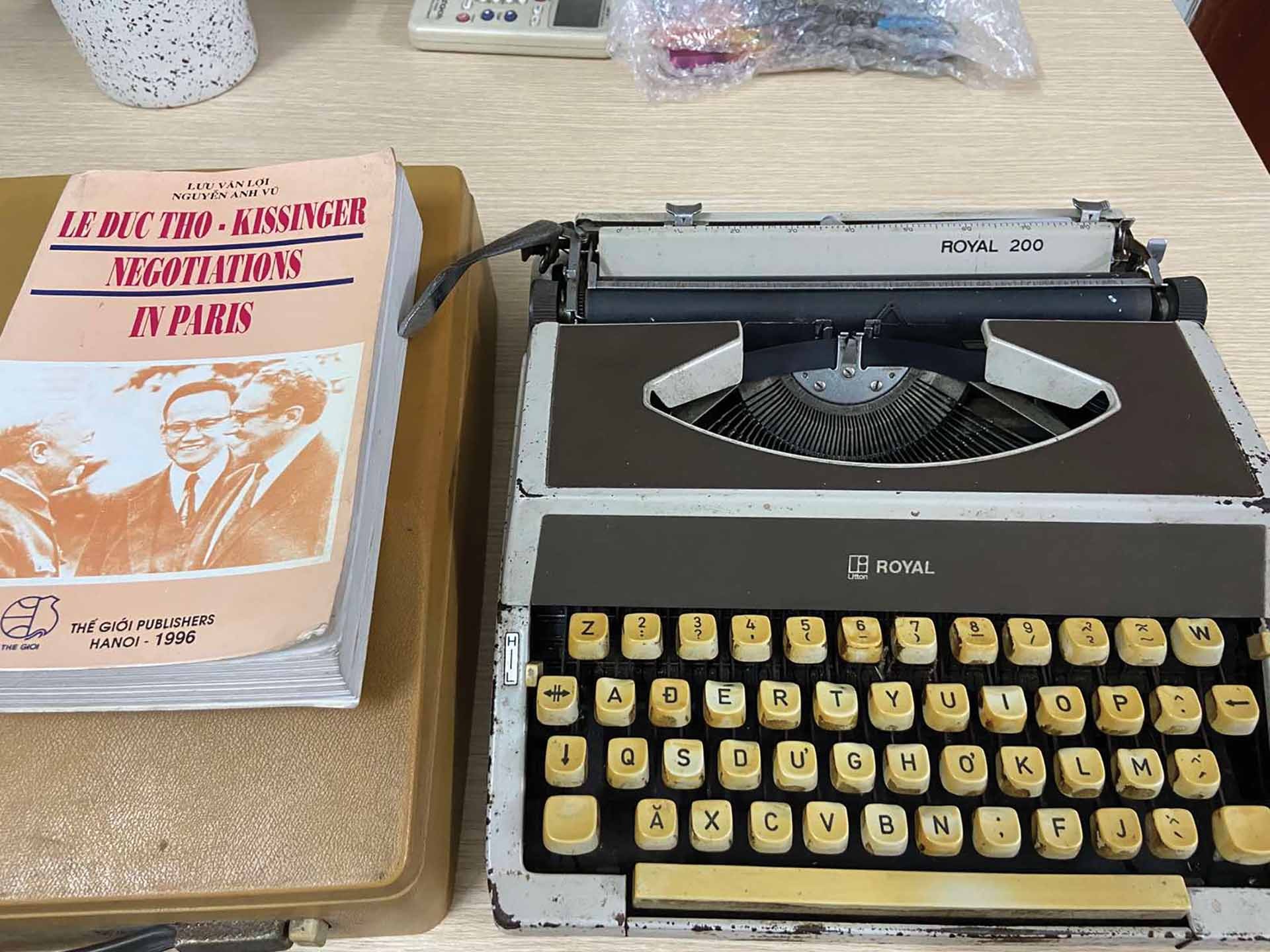

The modest office was “overflowing” with books - thick volumes covered in the dust of time, and an old-style English typewriter no bigger than a desk telephone - still there, but without his presence. Sipping a warm cup of tea, I was fortunate to sit with Uncle Hai (the eldest son of Mr. Phuong, who followed in his father’s footsteps) and his wife, immersed in stories about the life and career of that interpreter.

Persistent, humble, yet radiant

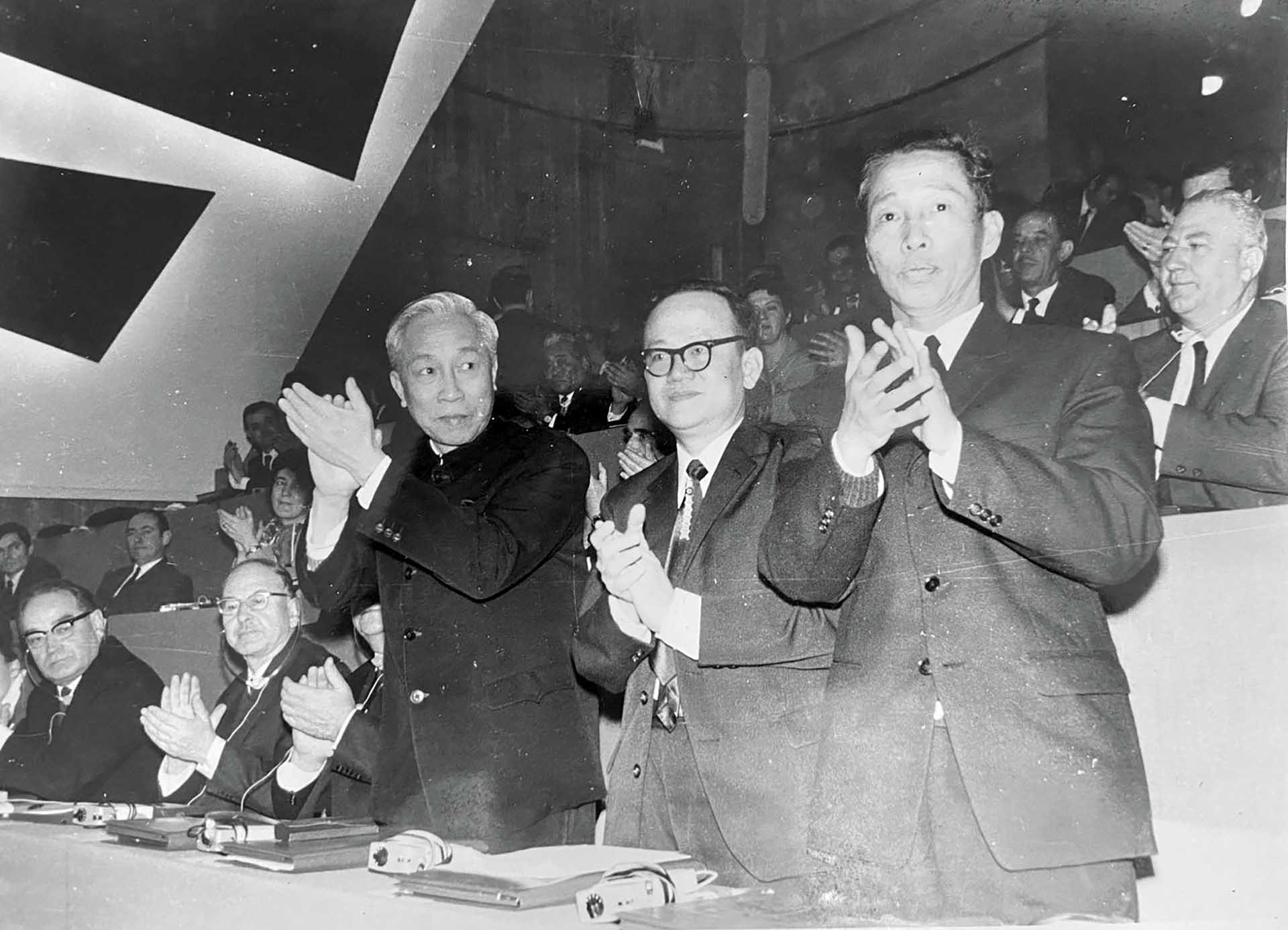

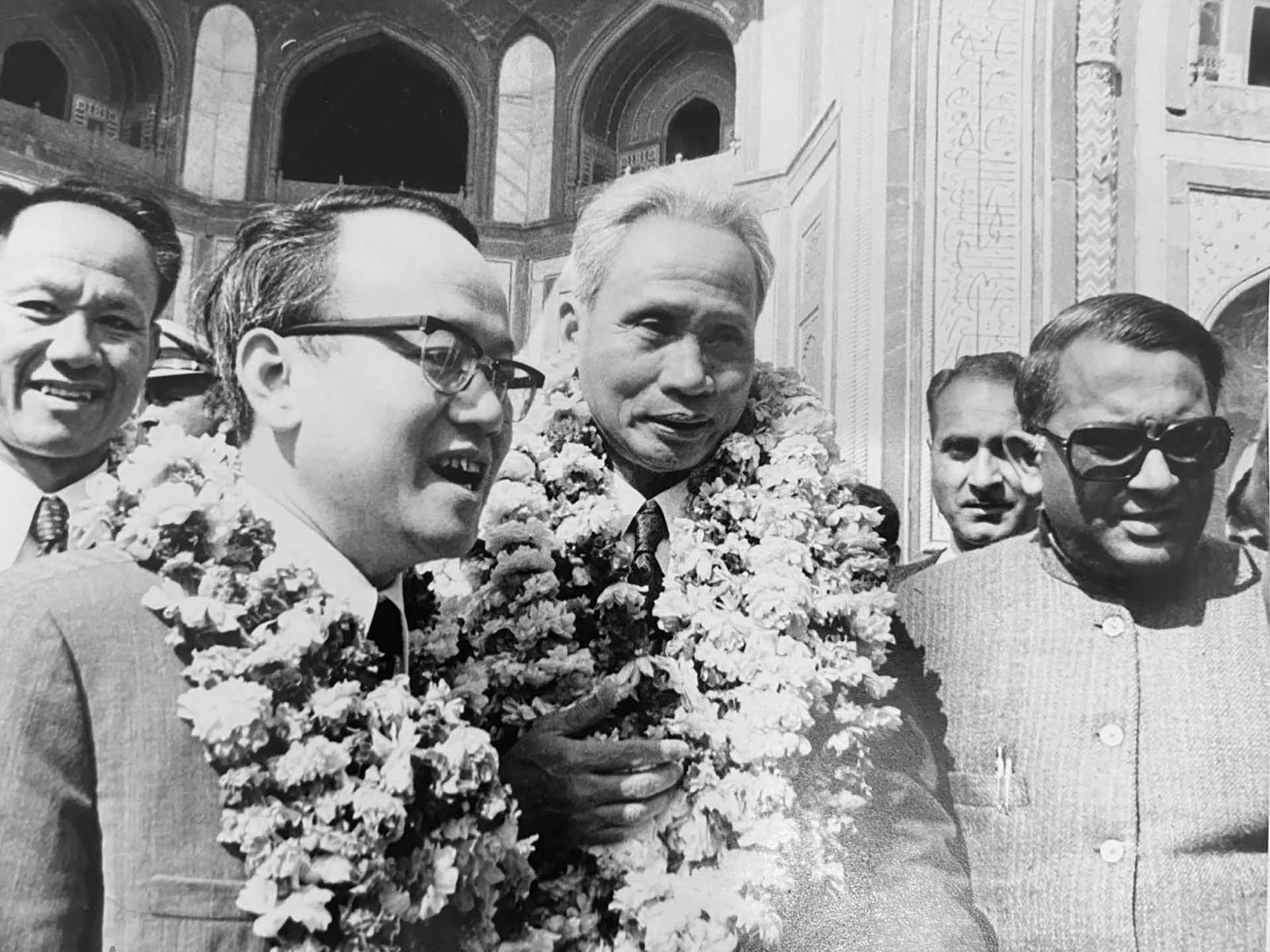

History books seldom devote much space to interpreters. Yet in many historic photographs, that interpreter stands in the middle, with bright eyes behind his glasses, a broad forehead, and a gentle smile. Mr. Phuong was not only an interpreter but also a direct witness to rare moments in the brilliant history of Vietnam’s diplomacy: the chief interpreter for secret negotiations and private meetings between Minister Xuan Thuy and Ambassador William Harriman and later between Special Adviser Le Duc Tho and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger, from 1968 until the spring of 1973.

His life reminds me of a “sun” - persistent, humble, and radiating its principle. He persevered in his mission as an interpreter and shone within it, modestly and quietly. A long chapter of his life was devoted to interpretation, including his years at the Paris Conference. Though he made vital contributions to the country’s historic events, he always considered them natural duties - work to be done and responsibilities to be fulfilled for the nation.

Even after retirement, and well into the final years of his life, he remained passionate about translation and his love for reading and collecting books. Every day, from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., except when ill, he would sit at his typewriter, writing and translating upon requests from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Vietnam News Agency, The Gioi Publishers, Van Hoa Publishers, Kim Dong Publishing House and others. Around the Van Mieu-Quoc Tu Giam area, locals were familiar with the image of an elderly man leisurely walking with a cane, cheerfully greeting people in all weather, making his way to the book street to expand his extensive collection of Western and Vietnamese literature, Vietnamese history, and world history and culture. Every penny he had went into books - his pension, his translation royalties - especially English literature and history books.

I believe he was a happy and fortunate man, for he lived his life fully with his passion. That happiness cannot be measured, but it appeared in every journey he took, in the satisfied smile in every photograph of him. In one article recounting the secret negotiations on the Paris Agreement, he expressed that fulfilment:

“Now, I feel truly content recalling the time when I served as a linguistic bridge between, on one side, representatives of the United States - a Western power with overwhelming economic, military, scientific, and technological strength - and, on the other, representatives of Vietnam - a small, poor, and underdeveloped Eastern nation, yet with a proud cultural and historical tradition”.

|

| Nguyen Dinh Phuong interpreted for Special Adviser Le Duc Tho at the Paris Conference. (Photo: Courtesy) |

It may not be “theory” for interpreters, but he summarised lessons that any interpreter would recognise:

“An interpreter must serve as a neutral medium in conveying language, striving not to reveal emotions through facial expressions or voice. However, when interpreting for Anh Sau (Le Duc Tho) in negotiations with Kissinger, I am not sure I always succeeded, for I was still a party to the talks. I only remember that throughout the process, I felt proud to interpret for Vietnam’s steadfast and brilliant representatives, who commanded respect and admiration from the other side after intense, prolonged battles of logic and intellect in the secret Paris negotiations”.

What he left his children and grandchildren was intangible but priceless - as valuable as his life and way of living. His simple, responsible, and dedicated lifestyle became an “unwritten rule” for his family. They are still proud of their father and grandfather for their quiet contributions to an important historical event of the nation. One of his granddaughters, while studying in the United States, was moved to tears upon entering a history professor’s office and seeing, prominently displayed on the desk, a photograph of that professor with her grandfather. In some way, his contributions to the Paris Conference were not entirely silent.

|

| Nguyen Dinh Phuong interpreted for Prime Minister Pham Van Dong. (Photo: Courtesy) |

The secret negotiations

We reminisced about the stories Mr. Phuong told of the secret negotiations at the Paris Conference between Special Adviser Le Duc Tho and Minister-Head of Delegation Xuan Thuy (Anh Sau, Anh Xuan), the men at the forefront of that historic diplomatic campaign. Mr. Phuong recounted them with deep respect and admiration for Vietnam’s “masters” of diplomacy, who always maintained initiative and creativity in negotiations.

Mr. Phuong once wrote: If Kissinger, a Harvard professor, was known worldwide as a disciple of Metternich (the Austrian diplomat who chaired the Congress of Vienna to redraw Europe) or of Machiavelli (the renowned Italian philosopher and politician), then Le Duc Tho’s biography was far simpler - like an Eastern folktale. Anh Sau never attended any prestigious school. His “school” was the school of practice - experience distilled from years of revolutionary work, beginning in his teens, until he became a professional revolutionary and an outstanding leader of the Communist Party of Vietnam. The spirit radiating from him inspired trust from comrades and respect from opponents.

One story from the secret talks remained vivid in Mr. Phuong’s memory: Once, Kissinger quietly chewed his pencil, listening to Anh Sau’s presentation while Mr. Phuong attentively conveyed every word. Suddenly, Kissinger asked:

“During your trips to Beijing and Moscow, surely your friends informed you of our views on these negotiations?”, a reference to President Nixon’s visits to China and the Soviet Union. Without hesitation, Anh Sau replied: “We fight your troops on the battlefield, and we negotiate with you at the conference table. Our friends fully support us, but they cannot negotiate in our place”.

Another time, when Anh Sau criticised Kissinger’s proposal for troop withdrawals as a step backward from earlier agreements, Kissinger said:

“Lenin said: One step back, two steps forward. I am following Lenin”.

Anh Sau retorted instantly:

“Leninism must be applied flexibly. You, on the other hand, are mechanical”.

Just a few short exchanges revealed Anh Sau’s fluent, flexible and sharp debating skills.

After the United States failed in its late December 1972 B-52 bombing campaign against Hanoi and Hai Phong, negotiations resumed, and Anh Sau returned to Paris.

On 8 January 1973, on the way to the meeting at Gif-sur-Yvette, he instructed:

“Today, our delegation will not greet the U.S. delegation at the door as usual. I will strongly criticise the U.S., say that the Christmas bombing was foolish. Make sure to translate that with the right spirit…”

At the meeting, he did exactly that. Although Mr. Phuong had been forewarned and had seen many instances of the Adviser’s firmness, he had never seen him unleash such a storm of condemnation - deceitful, foolish, treacherous, backstabbing - everything! Kissinger could only bow his head in silence. Eventually, he stammered:

“I heard those adjectives… I will refrain from using them here”.

Anh Sau, still in the position of victor, replied immediately:

“That was only part of it. The press has used much harsher words”.

Although professional rules required Mr. Phuong to translate accurately, truthfully, and objectively, avoiding any display of personal emotion, he later admitted:

“I am not sure, at that moment, that I could suppress my joy mixed with pride at Anh Sau’s decisiveness and Kissinger’s feeble defence”.

|

| The typewriter - a keepsake that accompanied Mr. Phuong for decades in his interpreting work. (Photo: Courtesy) |

After years of wrangling at the conference table, we finally secured the principled positions - the most difficult, prolonged, and complex being the presence of northern troops in the South. It was Le Duc Tho’s courage, talent, and resolve that gradually forced Kissinger to concede, ultimately abandoning the demand for northern troop withdrawal and moving on to protocol discussions, leading to the swift conclusion of the final round on 13 January 1973.

“On 27 January 1973, witnessing the signing of the Paris Agreement by the parties, I could not contain the surge of emotion in my heart. The burning wish of mine and my colleagues in the delegation had finally become reality. I breathed a sigh of relief, as though I had lifted a great weight off my shoulders after so many long months serving the negotiations”, Mr. Phuong recalled.

More than ten years have passed since Mr. Phuong’s passing. His office, with its typewriter covered by a fine layer of dust, still lacks its devoted owner. Yet the stories of his life, of the years he gave selflessly to the nation, will live on, for they have already become part of history.