The Nhat Binh Robe: From imperial court attire of the Nguyen Dynasty to a living cultural symbol

Latest

|

| The Nhat Binh robe was imperial court attire of the Nguyen Dynasty. |

When clothing became a language of power

From ancient times, attire has been more than mere covering; it has been a non-verbal language - silently expressing hierarchy, social order and even political authority. As historian Tran Duc Anh Son once observed, the ceremonial garments of the Nguyen court not only showcase exquisite craftsmanship but also act as “a mirror reflecting social relations”.

Upon ascending the throne in 1802, Emperor Gia Long sought not only to consolidate territory but also to codify court dress. Thus, the Nhat Binh was born - reserved exclusively for queens, princesses, and imperial consorts. Its rectangular collar, known as "co Nhat Binh", symbolized propriety and precision, distinguishing it from the rounded or crossed collars worn by commoners.

Every element of the robe carried layered meaning:

Color: The empress alone could wear pale yellow - a rare privilege, as yellow was reserved for the emperor. Princesses and consorts wore strictly prescribed hues of blue, pink, purple, or vermilion.

Motifs: Phoenixes, peacocks and loan-tri birds adorned female garments, while dragons were reserved for the sovereign. A robe featuring the phoenix instantly revealed the wearer’s noble rank.

Material: Brocade, satin, gauze, and gold-thread embroidery - fabrics of rarity and opulence - were privileges of the royal household.

Through the Nhat Binh, one sees not merely aesthetic refinement but a meticulously woven tapestry of courtly order, spun from threads of gold and jade.

Fashion or politics?

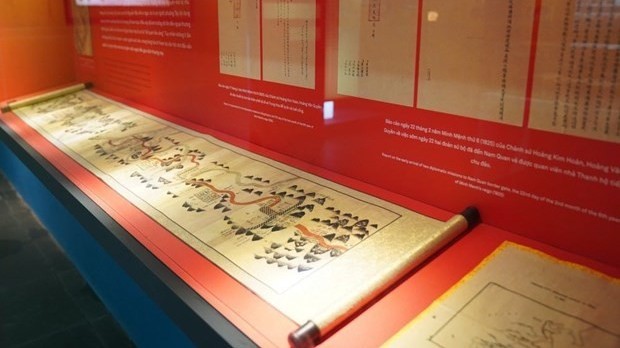

Clothing, in many instances, functions as a tool of power—and in the case of the Nhat Binh, this truth is striking. Consider Emperor Minh Mang’s decree banning the traditional skirt.

In 1827, Minh Mạng ordered northern women to abandon the traditional skirt and adopt wide-leg trousers—an element of the Nhat Binh. The edict provoked public outrage and inspired satirical folk verses:

“In the eighth month came the royal decree,

Banning the bottomless skirt-people trembled in fear…”

This episode vividly illustrates how fashion can serve as an instrument of political enforcement rather than personal choice.

The Nhat Binh also embodied the Confucian ideal of feminine virtue - the tu duc (four virtues): diligence, decorum, speech, and morality. With its square collar, symmetrical embroidery, and long flowing silhouette, the robe both celebrated and constrained women, reinforcing their roles as dutiful wives and mothers - subordinate to fathers, husbands and sons.

Scholars have described this as “symbolic power”: women appeared prominently in ritual, yet their authority remained ceremonial, while genuine political power stayed firmly in male hands.

|

| The Nhat Binh robe was created exclusively for queens, princesses and imperial consorts. Its rectangular collar, known as "co Nhat Binh", symbolized propriety and precision, distinguishing it from the rounded or crossed collars worn by commoners. |

Empowerment - bestowed, not claimed

The Nhat Binh reveals a duality. On one hand, it conferred honor upon royal women, granting them visible, dignified presence in state ceremonies. On the other, it reminded them that their prestige was granted, not self-earned - a reflection of the patriarchal order.

As researcher Dương Kim Anh (Vietnam Women’s Academy) observed: “The Nhat Binh was not merely ornamental; it reinforced hierarchy and delineated women’s roles. It was a subtle manifestation of Nguyen - era patriarchy”.

Thus, the robe serves as a “double mirror” - reflecting both the splendor of royal femininity and the boundaries society imposed upon it.

The Nhat Binh today: Echo or revival?

Though centuries have passed since it left the palace halls, the Nhat Binh remains vibrantly alive. In recent decades, it has reemerged across art, fashion and cultural life.

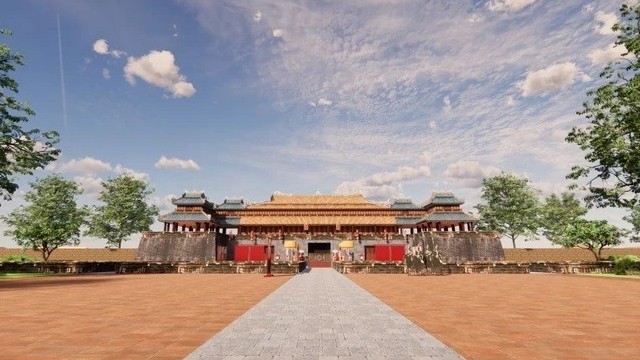

At cultural festivals, most notably Hue Festival, the grand celebration of the former imperial capital, the robe is revived through court-style performances. Visitors marvel as young women, clad in Nhat Binh, glide gracefully through the Dai Noi citadel, as if time itself had turned back.

In contemporary fashion, Vietnamese designers such as Ngo Nhat Huy have reinvented the Nhat Binh into wedding gowns and performance costumes - retaining the square neckline and phoenix patterns but blending them with modern lace and silk. The result is a dynamic fusion of tradition and modernity.

Among the younger generation, enthusiasm for the robe flourishes - from graduation photos and engagement ceremonies to historical cosplay collections shared online. For them, wearing Nhat Binh is not only an aesthetic choice but a means of reconnecting with cultural roots.

A timeless symbol

Today, the Nhat Binh no longer signifies rank or privilege. No one judges a woman’s social status by the color of her collar. Yet it endures for three profound reasons:

Aesthetic Symbol: It embodies the meticulous artistry of Vietnamese craftsmanship.

Cultural Symbol: It recalls a historical moment when attire itself was a language of politics.

Feminine Symbol: Once a garment of constraint, it has become an emblem of pride and identity for modern Vietnamese women.

Once defining a woman’s place within the imperial hierarchy, the Nhat Binh was both beautiful and austere—both empowering and limiting. Two centuries later, the dust of history has fallen away.

Today, it stands as a vibrant symbol of Vietnamese heritage—worn not in obedience, but in celebration of individuality, elegance, and national pride.

From a “language of power” in the imperial court, the Nhat Binh has transformed into a voice of freedom in the modern era.

References

· Tran Duc Anh Son (2015), Trang phuc cung dinh trieu Nguyen, Vietnam History Museum.

· Ngo Si Lien (2004), Dai Viet Su Ky Toan Thu, Cultural Information Publishing House.

· Duong Kim Anh, Luong Van Tuan, Penelopa Gjurchilova (2024), Gender and Equality Studies, Hanoi Law University – UNDP.

· Le Thai Dung (2015), “Why Did Emperor Minh Mang Ban Women from Wearing Skirts?”, Vietnam Women’s Newspaper Online.

· Vietnamese Folk Poems.

| Green and low-mission Vietnamese rice: New symbol of responsible production On June 5, Vietnam’s rice industry marked a significant milestone with the export of the first batch of rice under the brand “Green and Low-Emission ... |

| Former Vice President Nguyen Thi Binh conferred the title ‘Hero of Labour’ WVR - On the morning of August 25, at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs working building, during the 80th anniversary celebration of the diplomatic sector ... |

| Vietnam prioritises training for cultural industry workforce Vietnam boasts rich “soft power” assets, from diverse cultural heritage to traditional festivals, landscapes and crafts. |

| A boost for the development of Vietnam's cultural industry WVR - From Phuong My Chi's soulful singing in China to Duc Phuc's historic victory in Russia, and the record-breaking revenue from the war film ... |

| Building a destination brand for culture and art enthusiasts in Hanoi: Thang Long Imperial Citadel WVR - During the three days from 10 to 12 October, Thang Long Imperial Citadel will become a “common house” of world cultures where music, ... |