Cultural scholar Huu Ngoc: A shoulder-height stack of answers

Latest

|

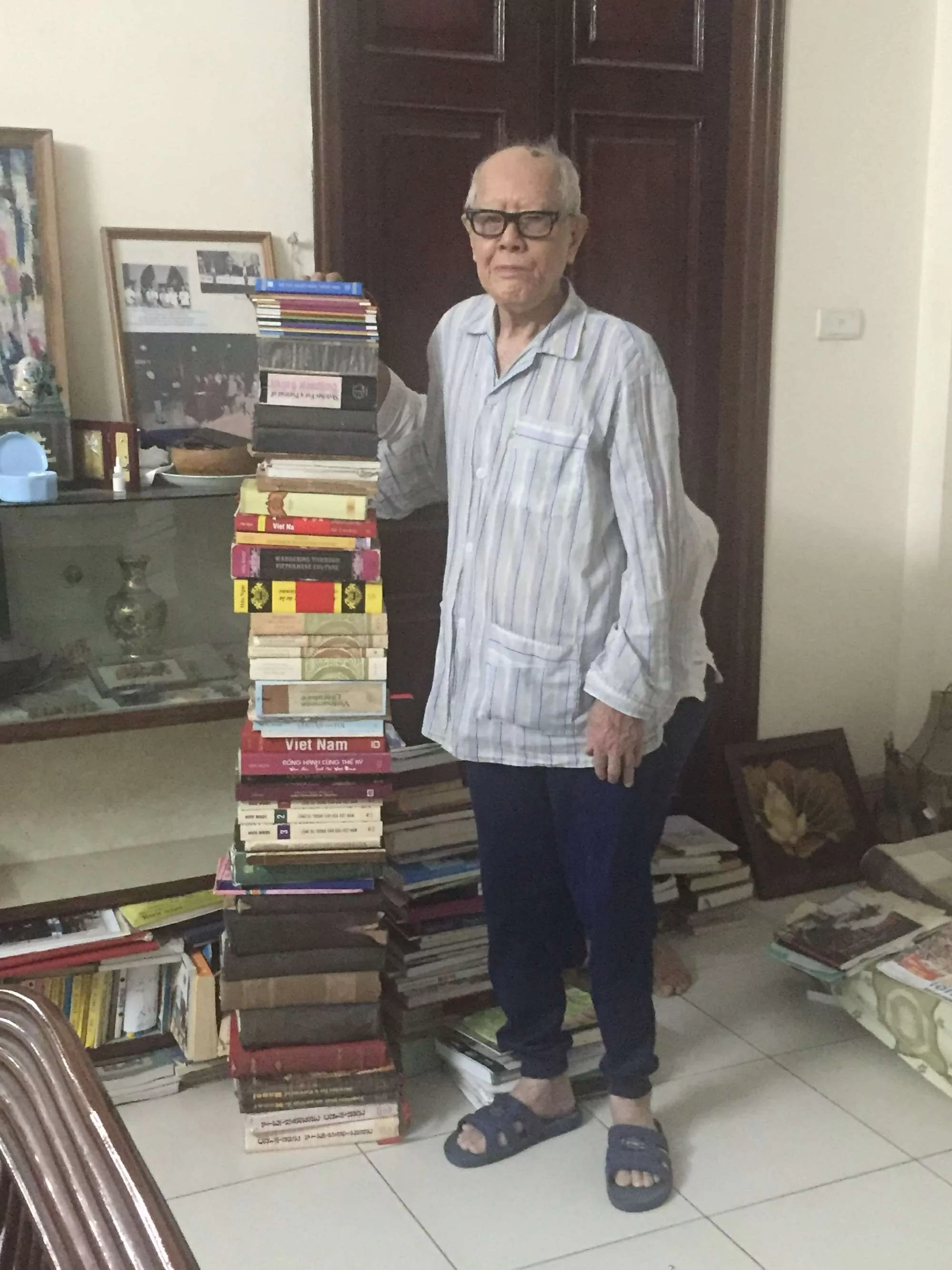

| Huu Ngoc's stack of authored books reached almost to his height. |

Cultural scholar Huu Ngoc (1918-2025) passed away on May 2, 2025. He had been living in his son's house, where he welcomed friends and colleagues into his airy room filled with mementos and books. If someone asked Huu Ngoc a question, he would cite which part of which book on which shelf in which bookcase held the answer.

Although blind and with little hearing, Huu Ngoc retained his extraordinary memory close to the end. Whenever I visited during recent years, his son Tien served as a hearing interpreter regardless of the language because those with little hearing can best understand a spouse or a grown child. Tien visited his father every day at his brother's house and worked with Huu Ngoc, recalling details of friends and projects to keep Huu Ngoc's memory strong.

I first met Huu Ngoc more than 50 years ago in Hanoi as the South was collapsing a province a day and I was leading what turned out to be the first and only delegation of American educators to visit North Vietnam. Over the years, Huu Ngoc and I worked together on projects while he was director of The Gioi Publishers and after he retired but continued to work full time. He quietly and constantly pushed the edges, helping Vietnam to move beyond rhetoric through his support of Vietnam's history and culture.

CHOICE (American Association of Publishers) featured Huu Ngoc's VIET NAM: Tradition and Change, edited by Elizabeth Collins and me and jointly published by Ohio University Press and The Gioi Publisher. The Vietnam Association of Publishers awarded VIET NAM: Tradition and Change a rare, double prize for content and design. Elizabeth Collins deserves credit for choosing essays from Huu Ngoc's 1,400-page Wandering Through Vietnamese Culture. Huu Ngoc then adjusted the draft contents. Phạm Tran Long, the book's editor and now Director of The Gioi Publisher, suggested the delightful drawings of traditional Vietnamese daily life from the Oger Collection (1990).

|

| Writer Lady Borton participated in a discussion session at the International Conference “50 years of National Reunification: The peace-building role of diplomacy in history and present”, organized by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, on April 23, 2025 in Hanoi. |

One afternoon seven years ago, Mary Pecaut and I were visiting Huu Ngoc in his room filled with books. With Huu Ngoc's agreement, Mary and I stacked all the books Huu Ngoc had written on foreign cultures (American, French, Japanese, Swedish, listed in alphabetical order) and on Vietnamese culture (editions of Wandering Through Vietnamese Culture in English, French, and Vietnamese; dictionaries; and books about Hanoi, ethnic minorities, and Vietnamese and foreign individuals whom Huu Ngoc admired). We excluded edited books and the many years of Vietnamese Studies quarterly, which he edited in English and French.

Huu Ngoc's stack of authored books reached almost to his height.

For some years, Huu Ngoc and I lived a block away from each other. For me, it was a twenty-minute bike ride to The Gioi. Huu Ngoc walked the length of traffic-jammed Kim Ma and onward, a battered bag of books on his shoulder. Retired as publisher, he had an office for the Swedish and Danish Cultural Funds at The Gioi Publisher on Tran Hung Dao.

Once, I asked him: "As you walk alongside that noisy traffic, are you writing in your head your next article for Viet Nam News?"

"No," he said. "I recite poetry."

Nearly two years ago, when I was in Hanoi and visited Huu Ngoc, his son Tien was out of the country. The attentive helper wanted Huu Ngoc to sign some career summaries, which I could take back to American friends. She was shouting (as was necessary), urging him to sign his name as "Nha Van Huu Ngoc" (Writer Huu Ngoc).

"No! I am not a writer!" he insisted, as I searched for one of his marker pens that might still have ink. "I am NOT a writer!"

Indeed, that is true. Huu Ngoc was not a writer.

English speakers translate "nha van" as "writer," but for Vietnamese, a "nha van" is a writer of fiction - that is, stories or novels. Those who write poetry, memoirs, biographies, histories, sketches, analyses, treatises, researched works, dictionaries, and translations have other descriptors.

The title Huu Ngoc used for himself was "nha van hoa" (cultural scholar).

Several months ago, when I was back in Hanoi and visited Huu Ngoc, he was less talkative but just as insistent. He was then aged 106. Because he was deaf, he could not hear his own voice. And so, whenever he spoke, he shouted.

"I don't want to work anymore!" he yelled.

I had not come to work but rather to sit on the bed, next to a longtime friend, close to his slightly hearing ear, my right arm around him to hold him up while Tien served as hearing interpreter. I placed a manuscript in his hands. He couldn't see, and he couldn't hear, but he could fan pages.

"How many pages?" he yelled, the editor/publisher immediately alert.

I had no idea. When he insisted, Tien picked up several of his father's books. We checked the number of pages and invented a figure for a manuscript still in process.

|

| Writer Lady Borton and friends at the funeral of Cultural Scholar Huu Ngoc, on May 5 in Hanoi. |

Now, these last few days, here again in Hanoi, I am finishing the index on that manuscript about People's War, which Huu Ngoc helped guide over the years. As I assign page numbers to entries, I think of Huu Ngoc and a conversation perhaps over twenty-five years ago, when we worked on Vietnam Cultural Window, his breakthrough magazine, which quietly challenged the then required rhetoric and allowed the more open voice common today.

The group of us working on Vietnam Cultural Window was walking down Ly Thuong Kiet to our favorite (and then the only) Hue restaurant. It was not unusual for us to go out together for lunch. The others, all Vietnamese, were ahead. Huu Ngoc and I walked side by side. Unbeknownst to me, one of the Vietnam Cultural Window staff had told Huu Ngoc that I was leaving (meaning going back to the States for good) as opposed to going on a work trip. And so, again, unbeknownst to me, Huu Ngoc thought we might never see each other again.

"Do you know why I write?" he said. His voice had a somber tone, like the sharing that comes between two long-term friends when one of them is dying.

"No," I said. "Why?"

"Because when I have a question, I know where to find the answer in one of my books."

Indeed, Huu Ngoc did know where to look up the answer to any question not only in his own books but throughout Vietnam and internationally, too. And he knew how to lead.

With his work as a publisher, editor, and author, we have his colleagues and friends' many stories and the shoulder-stack of his own books, which he filled with answers.

(Lady Borton, May 2025)