From Geneva to Paris: On the issue of strategic self-reliance

Latest

|

| Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai and Special Advisor Le Duc Tho in Beijing. (Photo: Archive) |

From the Geneva Conference

On May 8, 1954, exactly one day after the resounding victory at Dien Bien Phu, the Geneva Conference on Indochina opened in Geneva with the participation of nine delegations: the Soviet Union, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and China; the Democratic Republic of Vietnam; the State of Vietnam; the Kingdom of Laos; and the Kingdom of Cambodia. Vietnam repeatedly proposed inviting representatives of the Laotian and Cambodian resistance forces to the conference, but this was not accepted.

Regarding the context and intentions of the parties, it should be noted that the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States had reached its peak. Alongside the Cold War were hot wars on the Korean Peninsula and in Indochina and a trend toward international détente. On July 27, 1953, the Korean War ended, and Korea remained divided at the 38th parallel as before.

In the Soviet Union, after J. Stalin’s death in March 1953, the new leadership under Khrushchev adjusted foreign policy: pushing for international détente to focus on domestic issues. As for China, weakened after the Korean War, it embarked on its First Five-Year Plan for socio-economic development, sought to end the Indochina War, needed security in the south, wanted to break the encirclement and embargo imposed by the United States, push the US away from the Asian mainland, and assert its role as a major power in resolving international issues, especially in Asia.

France, after eight years of a costly war, wished to withdraw with honor while retaining its interests in Indochina. Domestically, anti-war forces calling for negotiations with Ho Chi Minh’s government were mounting pressure. The UK did not want the Indochina War to spread, fearing it would affect consolidation of the Commonwealth in Asia, and thus supported France.

Only the United States opposed negotiations, helping France intensify the war and increasing intervention. At the same time, it sought to draw France into the Western European defense system against the Soviet Union, hence supported France and the UK’s participation in the conference.

In this context, the Soviet Union proposed a Four-Power Conference of the Soviet, US, UK, and French foreign ministers in Berlin (January 25–February 18, 1954) to discuss the German question. However, that failed, so attention shifted to Korea and Indochina. Since these topics were discussed, the conference agreed—at the Soviet proposal—to invite China to participate.

For Vietnam, on November 26, 1953, answering Swedish Expressen reporter Svante Lofgren, President Ho Chi Minh expressed readiness to negotiate a ceasefire.

After 75 days of intense talks—8 plenary sessions, 23 smaller sessions, and numerous diplomatic contacts—the agreements were signed on July 21, 1954: three ceasefire agreements for Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, and the conference’s Final Declaration of 13 points. The US delegation refused to sign.

The main contents of the Agreement were that all parties recognized the independence, sovereignty, unity, and territorial integrity of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia; cessation of hostilities; prohibition on bringing in weapons, military personnel, and foreign bases; free general elections; France’s withdrawal ending colonial rule; the 17th parallel as a provisional military demarcation line in Vietnam; two regrouping zones in northern Laos for the resistance; demobilization in place for Cambodian resistance; and an International Commission for Supervision and Control composed of India, Poland, and Canada.

Compared with the Preliminary Agreement of March 6 and the September 14, 1946 Modus Vivendi, the Geneva Agreement was a major step forward and an important victory: France had to recognize Vietnam’s independence, sovereignty, unity, and territorial integrity and withdraw its troops. Half of the country was liberated, becoming a major rear base for the struggle for complete liberation and national reunification later.

While significant, the agreement had limitations, leaving costly lessons for Vietnamese diplomacy: independence and self-reliance combined with international solidarity; integrating political, military, and diplomatic strength; strategic study; and above all, strategic autonomy.

In the November 26, 1953 Expressen interview, President Ho Chi Minh stated: “… Negotiations on the ceasefire are primarily a matter between the Government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) and the French Government”. Yet Vietnam engaged in multilateral negotiations as one of nine parties, making it difficult to safeguard its own interests.

|

| General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Brezhnev receiving and holding talks with Special Advisor Le Duc Tho after he initialed the Paris Agreement on his way home, January 1973. (Photo: Archive) |

To the Paris Conference on Vietnam

In the early 1960s, major international developments occurred. The Soviet Union and Eastern European socialist countries continued to strengthen, but the Sino-Soviet split deepened, as did divisions in the international Communist and workers’ movement.

The national independence movement gained momentum in Asia and Africa. After the failure at the Bay of Pigs (1961), the US abandoned its “massive retaliation” strategy and adopted “flexible response” targeting liberation movements.

Applying “flexible response” in South Vietnam, the US waged “special war” to build a strong Saigon army with US advisors, equipment, and weapons.

When “special war” risked failure, in early 1965 the US landed troops in Da Nang and Chu Lai, launching “limited war” in South Vietnam. On August 5, 1964, the US also began bombing North Vietnam. The 11th (March 1965) and 12th (December 1965) Central Committee meetings affirmed the determination and policy of resistance against US aggression for national salvation.

After victories in the 1965–1966 and 1966–1967 dry season counter-offensives and in resisting the bombing of the North, our Party decided to shift to the strategy of “fighting while negotiating”. In early 1968, we launched the General Offensive and Uprising, which, though not achieving all objectives, dealt a heavy blow to US will.

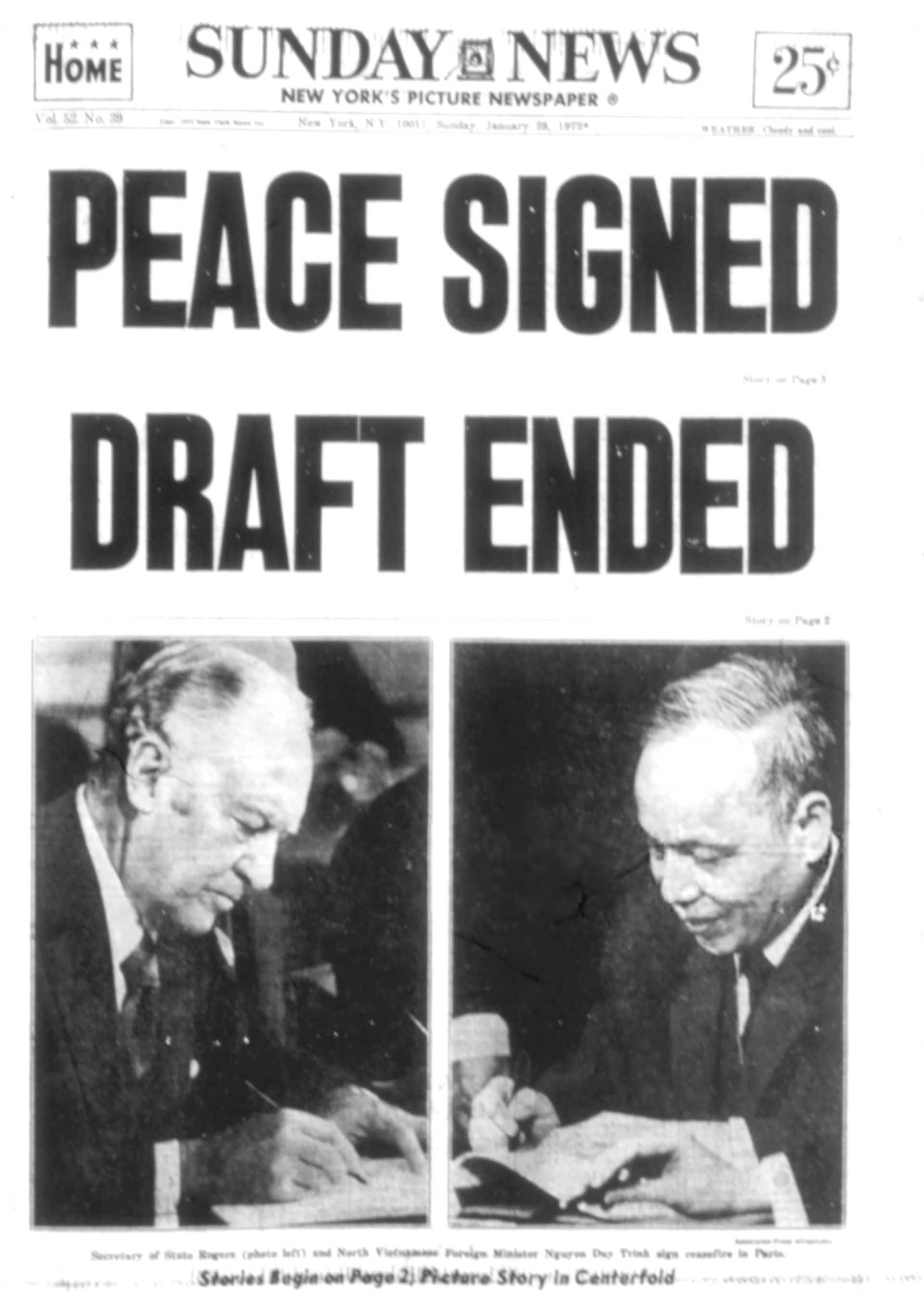

On March 31, 1968, President Johnson decided to halt bombing of North Vietnam and was ready to send representatives to talk with the DRV, opening the Paris talks (May 13, 1968–January 27, 1973)—the longest and most arduous diplomatic negotiation in Vietnam’s history.

The talks had two phases. First phase (May 13–October 31, 1968): DRV–US talks on the complete cessation of US bombing of North Vietnam.

Second phase (January 25, 1969–January 27, 1973): Four-party conference on ending the war and restoring peace in Vietnam, involving the DRV, the US, the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam/Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam, and the Saigon administration.

From mid-July 1972, Vietnam proactively moved to substantive talks to sign an agreement after the Spring–Summer 1972 campaign victory and as the US presidential election approached.

On January 27, 1973, the parties signed the Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam (9 chapters, 23 articles), plus 4 protocols and 8 understandings—meeting the Politburo’s four demands, especially US troop withdrawal while our forces remained.

The Paris negotiations left major lessons for Vietnamese diplomacy: independence and self-reliance with international solidarity; combining national and era strengths; diplomacy as a front; negotiation skills; public opinion struggle; strategic study—especially independence and self-reliance.

Learning from Geneva 1954, Vietnam formulated and implemented an independent and self-reliant resistance and foreign policy, while coordinating with fraternal countries. Vietnam directly negotiated with the US—this was the fundamental reason for the diplomatic victory in the resistance against the US. These lessons remain valid today.

|

| General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Brezhnev receiving and holding talks with Special Advisor Le Duc Tho after he initialed the Paris Agreement on his way home, January 1973. (Photo: Archive) |

Strategic self-reliance

Does the lesson of independence and self-reliance from the Paris talks (1968–1973) relate to the “strategic self-reliance” debated by international scholars today?

According to the Oxford Dictionary, “strategy” involves identifying long-term goals or interests and the tools to achieve them, while “self-reliance” reflects self-governance and independence from external influence. “Strategic self-reliance” refers to a subject’s independence and self-reliance in determining and pursuing its important, long-term goals and interests. Scholars have generalized and given various definitions of this concept.

In fact, the idea of strategic self-reliance was affirmed long ago by Ho Chi Minh: “Independence means we control all our affairs, without outside interference”. In his September 2, 1948 Independence Day message, he expanded the concept: “Independence without our own army, diplomacy, and economy is fake independence and unity, which the Vietnamese people will never accept”.

Thus, not only must Vietnam be independent, self-reliant, unified, and territorially whole, but its diplomacy and foreign policy must also be independent, free from domination by any force. In relations between Communist and workers’ parties internationally, he asserted: “Parties, whether big or small, are independent and equal, and should unite to help each other”.

He also clarified the link between international aid and self-reliance: “Our friends, above all the Soviet Union and China, have helped us selflessly and generously so that we may have more conditions for self-reliance”. To strengthen solidarity and cooperation, independence and self-reliance must come first: “A nation that does not rely on itself and just waits for others to help is unworthy of independence”.

Independence and self-reliance were consistent, central elements of Ho Chi Minh’s thought. The core principle was: “If you want others to help you, you must first help yourself”. Preserving independence and self-reliance is both a policy and an immutable principle in Ho Chi Minh’s ideology.

Drawing lessons from Geneva, Vietnam upheld the principle of independence and self-reliance in the Paris Agreement negotiations—Ho Chi Minh’s foundational foreign policy principle. This is precisely the “strategic self-reliance” now vigorously discussed by the international research community.