The Geneva Conference 70th Anniversary

Latest

|

| Vietnamese soldiers planted a flag on the roof of the De Castries tunnel in Dien Bien Phu, on May 7, 1954. (Source: Getty Images) |

In January 1954, a conference of the Big Four Foreign Ministers (Great Britain, France, United States and the Soviet Union) met in Berlin and agreed to convene a meeting in Geneva in April of the “Five Great Powers” (the Big Four plus the People’s Republic of China) and “other states concerned” to discuss the problem of restoring peace in Korea and Indochina. The Indochina phase of the conference opened on 8 May, a day after the French garrison at Dien Bien Phu fell to the Vietnam People’s Army.

Towards a ceasefire

The Geneva Conference brought an end to the war in Indochina because Great Britain, China, France and the Soviet Union (USSR) each separately reached the conclusion that a ceasefire would serve their respective national interests. Britain wished to see a resolution of the conflict fearing it could spill over and affect its colony in Malaya where it was facing a local communist-led insurgency (1). The Government of France, facing a population increasingly disenchanted with the “la sale guerre” (dirty war), was at the end of its electoral tether. A public opinion poll taken on 21 November 1953, for example, revealed that nearly sixty-seven percent of those who expressed an opinion were in favour of either negotiations or a French withdrawal [2].

The USSR and China shared a common fear that the war in Indochina would escalate, particularly as the United States was calling for a “united action” to intervene. The USSR also hoped to link a settlement in Indochina with negotiations over Europe, an area of greater strategic concern. [3]

|

| Professor Carlyle A. Thayer. |

Both the Soviet Union and China wished to encourage the momentum gained as a result of the armistice reached in Korea in July 1953. They both brought pressure on to bear on the leaders of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) to agree to negotiations with France [4]. In November 1953, Ho Chi Minh finally signaled that the DRV Government would support negotiations [5].

China had other reasons for wishing to see peace restored in Indochina. It did not want foreign military forces stationed in northern Vietnam. Also, at this time it was turning inward, concerned with a new five-year plan of economic reconstruction. [6]

The United States was initially opposed to an international conference to bring about an end to the war in Indochina. Diplomatic pressure from France and the United Kingdom, who both opposed “united action,” ultimately persuaded the U.S. to attend the Geneva conference.[7]

In brief, a constellation of the major powers each for its own national interests was simultaneously moving in a direction to obtain a ceasefire in Indochina.

TENSE NEGOTIATIONS

The Geneva Conference on Indochina was convened from May to July 1954. It was attended by representatives from France, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), the State of Vietnam, the Kingdom of Cambodia, the Kingdom of Laos, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, China, and the United States. The conference was co-chaired by Britain and the USSR. After the initial exchange of views, it was decided to separate political from military issues. Military issues were to be discussed in confidential talks between the representatives of the French and Vietnam People’s Army (VPA) High Commands.[8]

|

| Overview of the Geneva Conference in 1954. (Source: VNA) |

While the Geneva Conference was in session the Joseph Laniel Government in Paris fell on 19 June. Pierre Mendes-France became the new Prime Minister. He set a self-imposed deadline of thirty days for an agreement. He threatened that

if the deadline was not met he would resign from office but before doing so he would go to the National Assembly and support national conscription so France could fight on in Indochina.[9]

Both the Soviet Foreign Minister, Vyacheslav Molotov, and his Chinese counterpart, Zhou Enlai, intervened decisively at various stages of the conference to keep up the momentum.[10] Zhou Enlai lobbied Pham Van Dong, the DRV’s Deputy Prime Minister, into dropping his demand that the Khmer and Lao resistance forces be given separate recognition.

There were basically two solutions mooted for a settlement of the conflict. There were two proposals that received attention: regroupment into enclaves, the so-called “leopard spot” solution, and regroupment into separate zones.[11] Both sides favoured the latter and this led to the partition of Vietnam.

There can be no doubt that VPA and DRV military and political strength was greater in the north and central Vietnam than in the south. Any demarcation line drawn across Vietnam north of the thirteenth parallel would have cut across areas under the control of the DRV. According to the official edition of The Pentagon Papers:

During June and July [1954], according to CIA maps, Viet Minh forces held down the larger portion of Annam (excepting the major port cities) and significant pockets in the Cochinchina delta. Their consequent claims to all the territory north of a line running northwest from the 13th to the 14th parallel (from Tuy Hoa on the coast through Pleiku to the Cambodian border) was far more in keeping with the actual military situation than the French demand for the location of their partition line at the 18th parallel.[12]

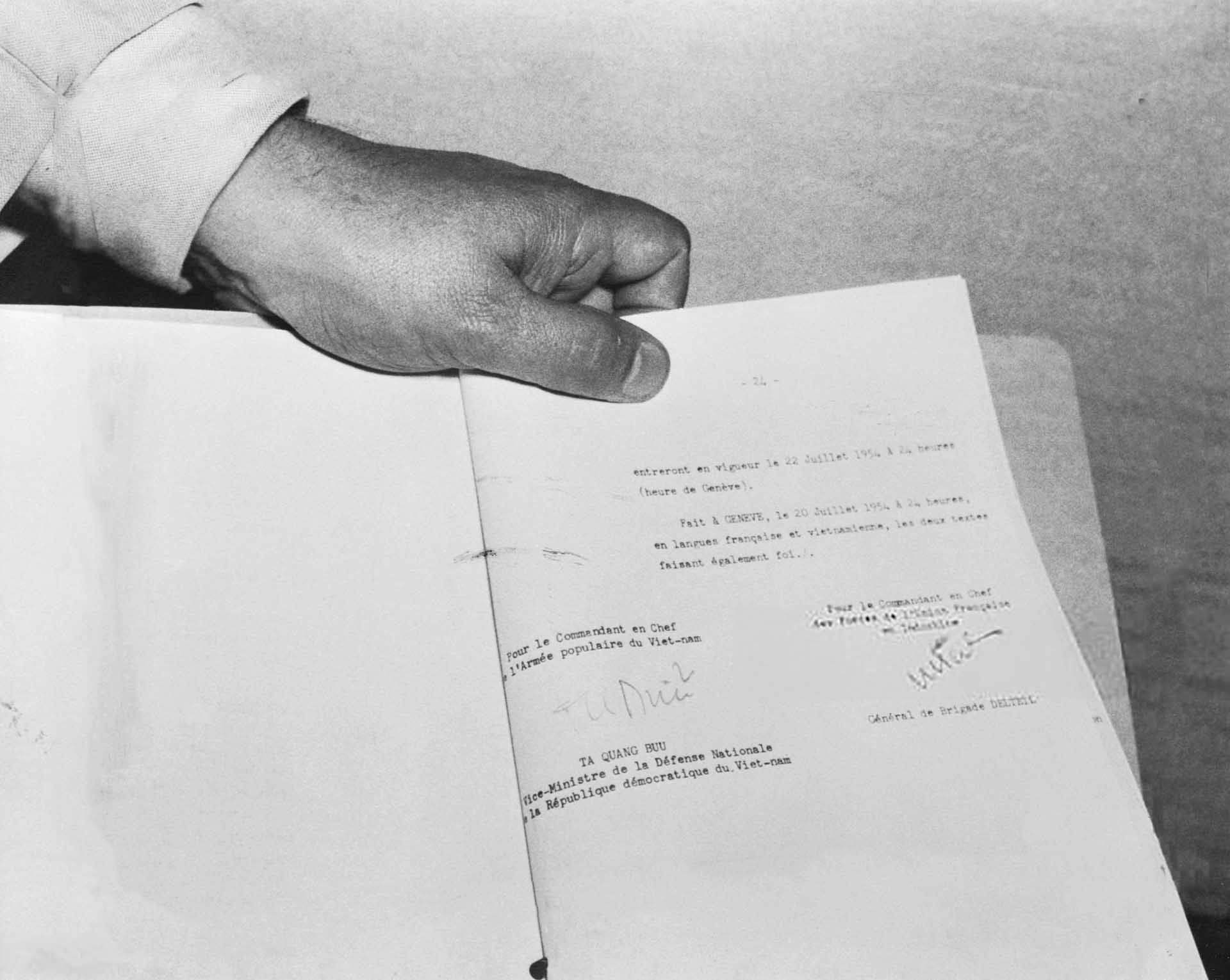

As a result of staff talks held by Western military officials, it was decided that a demarcation line drawn across central Vietnam at roughly 17o30’ north would be defensible.[13] DRV representatives were anxious to secure unified territory adjacent to China, with its own port and capital city.[14] It was clear from gestures made by Ta Quang Buu, a representative of the VPA High Command, at a secret military session held on 10 June with his French counterpart M. de Brébisson that the DRV was considering a line drawn at about the sixteenth parallel.[15] The French pushed for the eighteenth parallel.

During the course of late June/early July, Pham Van Dong pressed successively for the thirteenth, fourteenth, and sixteenth parallels. But it was only on 20 July, the deadline set by Mendès-France, that Molotov intervened and chose the seventeenth parallel – a compromise between the two. It was further stipulated that opposing military forces would regroup on either side of a demilitarized zone along the seventeenth parallel. French forces were to regroup to the south while communist forces were to regroup to the north, over a period of three hundred days.

The political provisions of the Geneva Agreements were much more ambiguous than the agreement on a military ceasefire. The vital clauses setting out the details on elections, for example, were included in the unsigned Final Declaration. The key provisions were contained in Point 7 that read: “General elections shall be held in July 1956 under the supervision of an international commission composed of representatives of the Member States of the International Supervisory Commission, referred to in the agreement on the cessation of hostilities. Consultations will be held on this subject between the competent representative authorities of the two zones from July 20, 1955 onward.”[16]

|

| General Henri Delteil, representing France, and Ta Quang Buu, Deputy Defense Minister of the DRV, signed the historic ceasefire agreement in Geneva. (Source: Getty Images) |

THE OUTCOME FOR THE FUTURE

The Geneva Conference on Indochina essentially focused on a ceasefire and the regrouping of military forces. The political aspects of the peace settlement were hastily drawn up. Unlike the ceasefire agreement, which was signed by representatives of the French and VPA High Commands, the Final Declaration, which contained the political terms of the settlement, was unsigned and adopted by voice vote.

In sum, the Geneva Agreements brought an end to armed conflict and resulted in the separation of opposing military forces. The French withdrew from northern Vietnam to below theseventeenth parallel. The Democratic Republic of Vietnam was now established with a unified territory, a capital, access to the sea, and a border with the People’s Republic of China.

The military victory at Dien Bien Phu and the diplomatic victory at the Geneva Conference did not lead to the

immediate reunification of Vietnam. When the deadline for the commencement of consultations between the “competent representatives” of Vietnam approached in July 1955, the DRV found itself an orphan. Both of the cochairmen of the Geneva Conference, Britain, and the Soviet Union, preferred to maintain the status quo. Thus, Vietnam remained partitioned for another two decades, alongside a divided Germany and a divided Korea.

*The Author is an Emeritus Professor of Politics at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of New South Wales, Australia, a renowned international relations and defense security scholar. He is a member of the Advisory Board for the Australia-Vietnam Leaders Dialogue (formerly the Australia-Vietnam Young Leaders Dialogue).

- Anthony Eden, Full Circle (London: Cassell Publishers, 1960), 87.

- Vincent Auriol, Journal de September 1947-1954, Vol. 7 (Paris: Armand Colin, 1971), 474 and 819.

- New Times [Moscow], July 31, 1958, 1 and supplement, 8.

- Mark Moyer, Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954-1965 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008),30 and 427, note 71 and Tillman Durdin, dispatch from Geneva, The New York Times, July 25, 1954.

- “Replies to a Swedish Correspondent (November 1953),” in Ho Chi Minh, Selected Writings, 1920-1969 (Hanoi: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1973), 153-154.

- Speech by Chen Yun, March 5, 1954, cited in Geoffrey Warner, “The 1954 Geneva Agreements: An Ambiguous Legacy,” Paper presented to the Contemporary China Centre Seminar Series, Research School of Pacific Studies, The Australian National University, Canberra, September 26, 1974. Chen Yun helped draft China’s First Five-Year Plan.

- Dwight D. Eisenhower, The White House Years: Mandate for Change, 1953-1956 (New York: Signet Books, 1965), 403-452,

- Robert F. Randle, Geneva 1954: The Settlement of the Indochinese War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 274-280.

- Philippe Devillers and Jean Lacouture, End of a War: Indochina, 1954 (London: Pall Mall Press, 1969), 246.

- Bui Tin, Following Ho Chi Minh: Memoirs of a North Vietnamese Colonel (London: Hurst & Company, 1995), 23.

- Devillers and Lacouture, End of a War, 207, 224, 250, and 259 and Randle, Geneva, 203.

- The Outcome for the Communists,” in United States-Vietnam Relations (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1971), Book 2, III.D.I, D8-D9. This is the official U.S. government version of The Pentagon Papers.

- U.S. Department of State, TEDUL 222, June 18, 1954, to the American Consulate in Geneva in U.S. Department of Defense, United States-Vietnam Relations (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1971), Book 9, 577 and T. B. Millar, ed. Australian Foreign Minister: The Diaries of R. F. Casey 1951-60 (London: Collins Publisher, 1972), 147.

- Devillers and Lacouture, End of a War, 233-234.

- Devillers and Lacouture, End of a War, 249-253.

- Final Declaration,” Point 7 in Great Britain, Further Documents Relating to the Discussions of Indochina at the Geneva Conference, Misc. No. 20, Command Paper Cmd. 9239 (London: HMSO, 1954), 9-11.